History of the Library

The Voltaire Library is the only library of an important French Enlightenment author to have been preserved intact.

Immediately following the death of Voltaire, Catherine II decided to buy his library in an attempt to bolster her reputation in Europe as a tolerant and enlightened ruler.

Catherine announced that she intended to build, at Tsarskoye Selo, her Summer Palace, a replica of Voltaire’s château in Ferney, which is located on the border between France and what was at the time the Republic of Geneva (today part of Switzerland), and where the writer spent the last twenty years of his life. The library was to be installed in this building.

‘Please send me the facade of the Ferney château and, if possible, the layout of the apartments inside. For either the park of Tsarskoye Selo will not exist, or the Ferney château will come and take its place. I must also know which rooms of the château face the north and which the south, the east and the west, and it is also crucial to know if Lake Geneva can be seen from the château windows, and from which side, likewise for Mount Jura’, she wrote to baron Friedrich Melchior Grimm, her literary and political agent in Europe. The plans never came to fruition, Catherine being satisfied with having acquired the philosopher’s books and manuscripts.

The library was sold by Marie-Louise Denis, Voltaire’s niece and heir. The terms of sale, negotiated by F. M. Grimm and Ivan Shuvalov, netted her the tidy sum of 135 398 livres tournois, 4 sols and 6 deniers, the equivalent of 30 000 gold roubles, and in addition a coffer of furs, jewels and a portrait of the empress studded with diamonds.

In 1779 the books travelled over ground to Lübeck, and from there to St Petersburg by a boat specially chartered by Catherine II for the occasion.

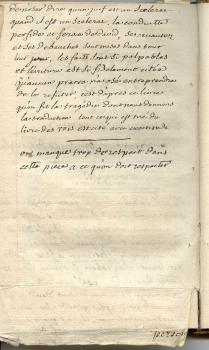

The matter of packing the books and moving them was left to Jean-Louis Wagnière, Voltaire’s faithful secretary and friend. Wagnière was the writer’s right-hand man, and well informed about all his projects. He knew the library inside out and had played an important role in compiling the catalogue of its contents, the ‘Catalogue de Ferney’, the manuscript of which is held today in the National Library of Russia.

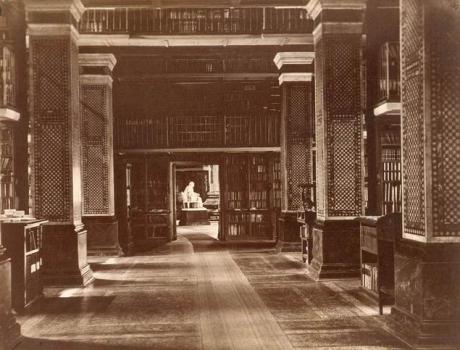

Wagnière arranged the books in a room adjacent to Catherine’s apartments in the Winter Palace (today, the Hermitage Museum), and he gave the keys into the care of Alexander Luzhkov, the empress’s librarian, an erudite man who was a skilled translator of French and English into Russian. Having received many gifts, as well as a pension for life, Wagnière returned to France in early 1780.

Catherine II died in 1796 and Luzhkov resigned when the new emperor mounted the throne. The library remained at the Hermitage, where it was moved to a new location, beneath the ‘Raphael loggias’.

The library was in those days shown to visitors from abroad as one of the curiosities of the Russian capital. During the reign of Nicholas I, who considered Voltaire to have been the responsible for the fall of the ancien régime, it was no longer open to visitors. Only the poet Alexander Pushkin, who had been appointed historiographer, was granted exceptional access to the collection. On 24 February 1832, he wrote to the Chiefs of Gendarmes, Alexander von Benckendorff, requesting permission to ‘consult the library of Voltaire, who had consulted books and rare manuscripts sent to him by [Ivan] Shuvalov to enable him to write his History of Peter the Great, and which is located in the Hermitage’.

Pushkin was therefore mainly interested in the manuscripts sent to Voltaire by the St Petersburg academicians, as well as in the Rossica – works about Russia – but he did also look at many other volumes and he copied down excerpts from the catalogue that had been established at the Hermitage.

In 1837, a court minister decreed that: ‘No one, apart from members of the imperial family, may borrow books from the Hermitage library without written permission; those wishing to conduct scientific research will be authorised to work in the library, but it is forbidden to consult books from the libraries of Voltaire and Diderot, or to take extracts from them.’

During the reign of Nicholas I, a tacit ban was imposed on any reference to Voltaire’s library in the press, although articles on the philosopher did occasionally appear in Russian periodicals.

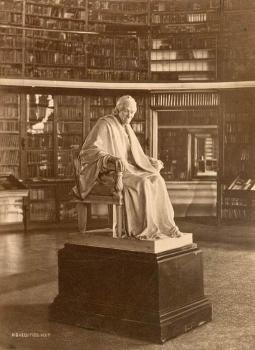

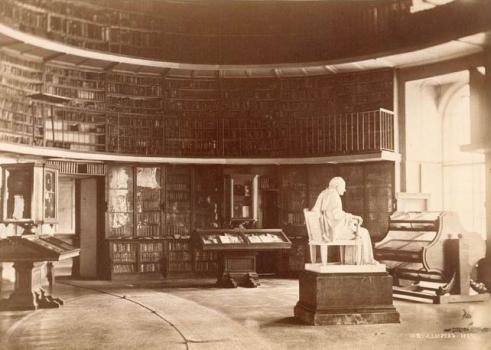

A particular focus of Nicholas’s hatred seems to have been the statue depicting the seated Voltaire, by Jean-Antoine Houdon, which was kept near the Ferney library. The bibliophile Rudolf Minzlov wrote, in his Stroll through the Imperial Public Library, that ‘under the emperor Nicholas I, this friend of Catherine’s was no longer a favourite in the Winter Palace. He travelled from corner to corner and, in spite of this, through the vagaries of chance, this marble statue was continuously in the path of the emperor’. Voltaire’s famous smile is said to have so irritated Nicholas I that he ordered that ‘the old monkey be taken away’!

The statue then left the Hermitage, and first found a refuge in the basement of the Tauride Palace, before being reunited, in May 1862, with the philosopher’s books, which had just been moved into the Imperial Public Library (the present-day National Library of Russia).

The transfer of the Voltaire Library to the Imperial Public Library took place under Alexander II, in late 1861. Baron Korf, director of the library, received a notification from the court minister indicating that ‘His Majesty the Emperor, because of the need to place rare and precious artworks in the Hermitage […], has ordered that, of the libraries which are in the Hermitage, Voltaire’s library included, [must only] be left [in the Hermitage] those editions concerned with fine art, its history, and archaeology, as well as the Russian library established for the use of the servants. All the other abovementioned collections, as well as all the manuscripts held in the Hermitage, and not excluding those illustrated with painted miniatures, are to be moved to the Imperial Public Library’.

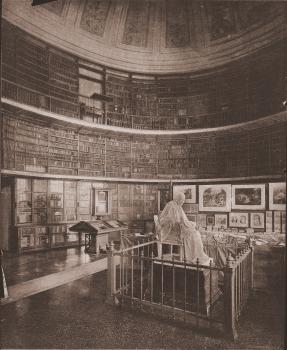

The Voltaire Library was installed in the oval room on the first floor (which today houses the Russian collection). The Houdon statue was kept in this room as well until 1887, when it was moved back to the Hermitage.

During the Second World War, the library was evacuated to the city of Melekess on the Volga (Dimitrovgrad today), and upon its return to Leningrad (now St Petersburg once more), it became part of the Rare Books Department.

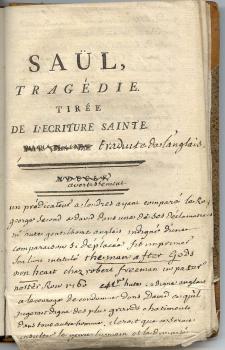

The Voltaire Library comprises 6814 volumes, manuscripts included. More than a third of the printed books contain notes (marginalia, from the Latin margo, margin) in the hand of their former owner. In fact, the notes are not always written in the margins, but sometimes on labels on the spines of the books, on title pages, endpapers, half titles, bookmarks, etc. There are blank bookmarks too, some of which are old bits of paper that Voltaire had to hand – playing cards, accounting papers, draft letters, strips torn from news-sheets. The pages can be dog-eared, and one finds flowers and blades of grass also used as bookmarks, not to mention coffee stains…

Voltaire’s library is not the collection of a bibliophile: it is, rather, the working library of a writer. It is made up mainly of eighteenth-century editions. Most of the books were acquired over the course of the last twenty years of the philosopher’s life, spent in Ferney, though many volumes were acquired before this period.

Books with historical subjects dominate in this library, particularly books on French history (nearly a quarter of the total). About the same number have to do with literature and art (French literature and theatre of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are best represented). Works of theology, Church history and canon law constitute about a fifth of the library. Philosophy is present in a comparable, if lesser, proportion. The works of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thinkers are present: Rousseau, Diderot, Helvétius, d’Holbach, Montesquieu, Bayle, Pascal, Descartes, Malebranche, Locke, Hume, Toland and Leibniz, amongst others.

This library was used by its owner as a working tool in the composition of his own writings: histories, philosophical works, plays, tales, poems and pamphlets. Wagnière, in his memoirs, reminisces: ‘M. de Voltaire had a prodigious memory. A hundred times he told me: “Look in this book, in this volume, around this page, to see if there is not something about such-and-such?” and he was very rarely wrong, even when he had not opened the book for twelve or fifteen years.’

The library contains a large number of historical sources, including many Rossica. One characteristic, which shows the working nature of the library, is the presence of many composite volumes that Voltaire called ‘pot-pourris’, in which he bound together sections of books and periodicals on topics of interest.

In 2003, the Voltaire Library was granted new quarters in the National Library of Russia thanks to a Franco-Russian collaboration initiated by Nikolai Kopanev, then director of the Rare Books Department, and supported by the Russian and French governments of the time (in particular President Jacques Chirac). The renovations began in 2001 and were completed in 2003. The rooms’ inauguration coincided with the tercentenary of the founding of St Petersburg, and took place on 28 May 2003, with the Prime Ministers of both countries, Mikhail Kassianov and Jean-Pierre Raffarin, in attendance. The Centre for the Study of the Enlightenment, was opened in the same location in 2004. Since then, the international conference Lectures voltairiennes brings together scholars from many different countries.

The Voltaire Library is open to visitors and researchers. It aims to embody and carry on the tradition of Voltaire’s spirit and values: culture, intelligence, tolerance and openness to the world.